- October 13, 2021

- Posted by: admin

- Category: BitCoin, Blockchain, Cryptocurrency, Investments

How Satoshi Nakamoto’s Bitcoin project married the concepts of digital cash and digital gold and how pioneering cryptographer Adam Back continues the work of making it a better tool for freedom.

One summer day in August 2008, Adam Back got an email from Satoshi Nakamoto.

It was the first time Nakamoto had reached out to anyone about a new project that the pseudonymous programmer or group of programmers called Bitcoin. The email described a blueprint for what a group of privacy advocates known as the cypherpunks considered the Holy Grail: decentralized digital cash.

By the mid-2000s, cryptographers had for decades tried to create a digital form of paper cash with all of its bearer asset and privacy guarantees. With advances in public-key cryptography in the 1970s and blind signatures in the 1980s, “e-cash” became less of a science fiction dream read about in books like “Snowcrash” or “Cryptonomicon” and more of a possible reality.

Censorship-resistance was a key goal of digital cash, which aimed to be money beyond the reach of governments and corporations. But early projects suffered from a seemingly inescapable flaw: centralization. No matter how much cutting-edge math went into these systems, they ultimately still relied on administrators who could block certain payments or inflate the monetary supply.

More “ecash” advances occurred in the late 1990s and early 2000s, each one making a critical step forward. But before 2008, a vexing computing riddle prevented the creation of a decentralized money system: the Byzantine Generals Problem.

Imagine that you are a military commander trying to invade Byzantium hundreds of years ago during the Ottoman Empire. Your army has a dozen generals, all posted in different locations. How do you coordinate a surprise attack on the city at a certain time? What if spies break through your ranks and tell some of your generals to attack sooner, or to hold off? The entire plan could go awry.

The metaphor translates to computer science: How can individuals who are not physically with each other reach consensus without a central coordinator?

For decades, this was a major obstacle for decentralized digital cash. If two parties could not precisely agree on the state of an economic ledger, users could not know which transactions were valid, and the system could not prevent double-spending. Hence all ecash prototypes needed an administrator.

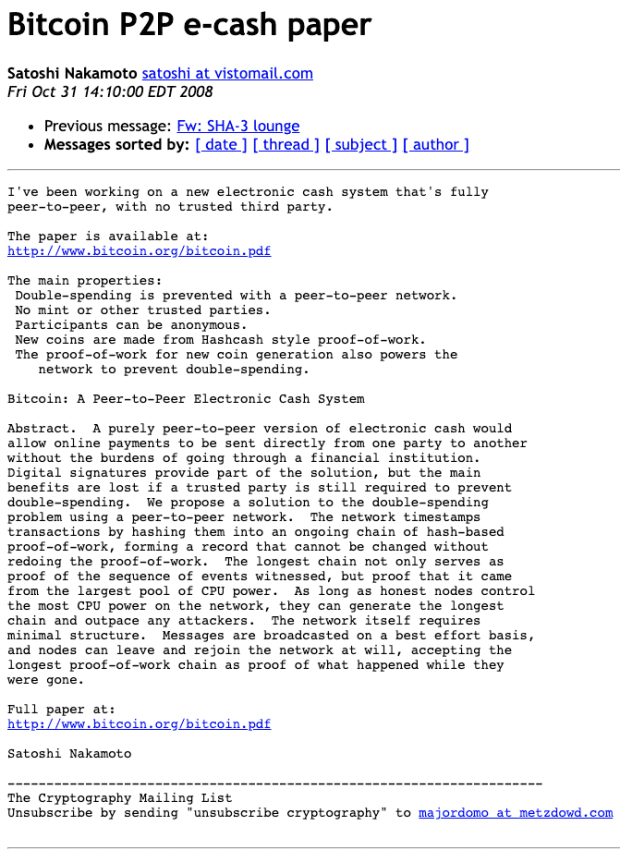

The magic solution came in the form of a mysterious post on an obscure email list on Friday, October 31, 2008, when Nakamoto shared a white paper, or concept note, for Bitcoin. The subject line was “Bitcoin P2P e-cash paper” and the author wrote, “I’ve been working on a new electronic cash system that’s fully peer-to-peer, with no trusted third party.”

To solve the Byzantine Generals Problem and issue digital money without a central coordinator, Nakamoto proposed to keep the economic ledger in the hands of thousands of individuals around the world. Each participant would hold an independent, historical, and continually-updating copy of all transactions that Nakamoto originally called a timechain. If one participant tried to cheat and “double-spend,” everyone else would know and reject that transaction.

After raising eyebrows and objections with the white paper, Nakamoto incorporated some final feedback and, a few months later on January 9, 2009, launched the first version of the Bitcoin software.

Today, each Bitcoin is worth more than $55,000. The currency boasts a daily transaction total greater than most countries’ daily GDP and a total market capitalization of more than $1 trillion. Nakamoto’s creation is used by more than 100 million people across nearly every country on earth and has been adopted by Wall Street, Silicon Valley, D.C. politicians, and even nation-states.

But in the beginning, Nakamoto needed help, and the first person they reached out to for assistance was Adam Back.

I. The Birth Of The Cypherpunks

Back was one of the cypherpunks, students of computer science and distributed systems in the 1980s and 1990s who wanted to preserve human rights like the right to associate and the right to communicate privately in the digital realm. These activists knew that technologies like the internet would eventually give enormous power to governments and believed cryptography could be the individual’s best defense.

By the early 1990s, states realized that they were sitting on an ever-growing treasure trove of personal data from their citizens. Information was often collected for innocuous reasons. For example, your Internet Service Provider (ISP) might collect a mailing address and phone number for billing purposes — but then hand this identifying information along with your web activity to law enforcement without a warrant.

The collection and analysis of this kind of data spawned the era of digital surveillance and eavesdropping, which, two decades later, led to the intricate and highly-unconstitutional war on terror programs that would eventually be leaked to the public by the NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden.

In his 1983 book “The Rise Of The Computer State,” New York Times journalist David Burnham warned that computerized automation could lead to an unprecedented level of surveillance. He argued that in response, citizens should demand legal protections. The cypherpunks, on the other hand, thought the answer was not to lobby the government to create better policy but instead to invent and use technology that the government could not stop.

The cypherpunks harnessed cryptography to trigger social change. The idea was deceptively simple: political dissidents from across the world could gather online and work together pseudonymously and freely to challenge state power. Their call to arms was: “Cypherpunks write code.”

Once the exclusive domain of militaries and spy agencies, cryptography was brought into the public world in the 1970s through academics like Ralph Merkle, Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman. At Stanford University in May 1975, this trio had a eureka moment. They figured out how two people could trade private messages online without needing to trust a third party.

One year later, Diffie and Hellman published “New Directions In Cryptography,” a seminal work that laid out this private messaging system that would become key to defeating surveillance. The paper described how citizens could encrypt and send digital messages without fear of snooping governments or corporations figuring out the contents:

“In a public-key cryptosystem enciphering and deciphering are governed by distinct keys, E and D, such that computing D from E is computationally infeasible (e.g. requiring 10100 instructions). The enciphering key E can be disclosed [in a directory] without compromising the deciphering key D. This enables any user of the system to send a message to any other user enciphered in such a way that only the intended recipient is able to decipher it.”

In simple terms, Alice can have a public key that she posts online. If Bob wants to send a private message to Alice, he can look up her public key, and use it to encrypt the message. Only she can decrypt the note and read the text inside. If a third party, Carol, does not have the private key (think: password) for the message, she cannot read the contents. This simple innovation changed the entire information power balance of individuals versus governments.

When Diffie and Hellman’s paper was published, the U.S. government, through the NSA, tried to prevent the spread of its ideas, even writing a letter to a cryptography conference at the time, warning the participants that their participation might be illegal. But after activists printed hard copies of the paper and distributed them around the country, the Feds backed off.

In 1977, Diffie, Hellman, and Merkle would file U.S. patent number 4200770 for “public-key cryptography,” an invention that created the foundation for email and messaging tools like Pretty Good Privacy (PGP) and today’s popular Signal mobile app.

It was the end of government control of cryptography and the beginning of the cypherpunk revolution.

II. The List

The word “cypherpunk” did not appear in the Oxford English Dictionary until 2006, but the community began gathering much earlier.

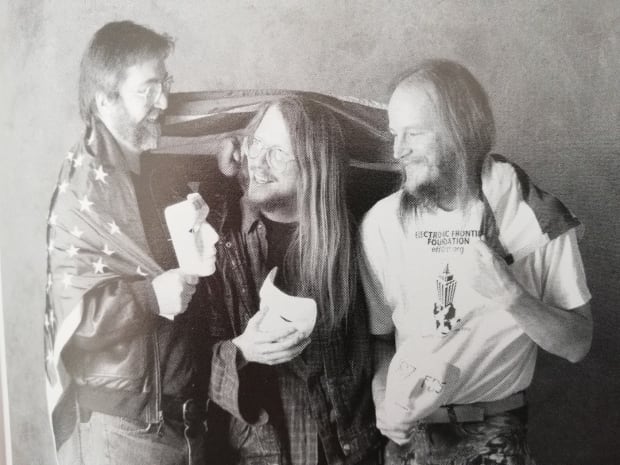

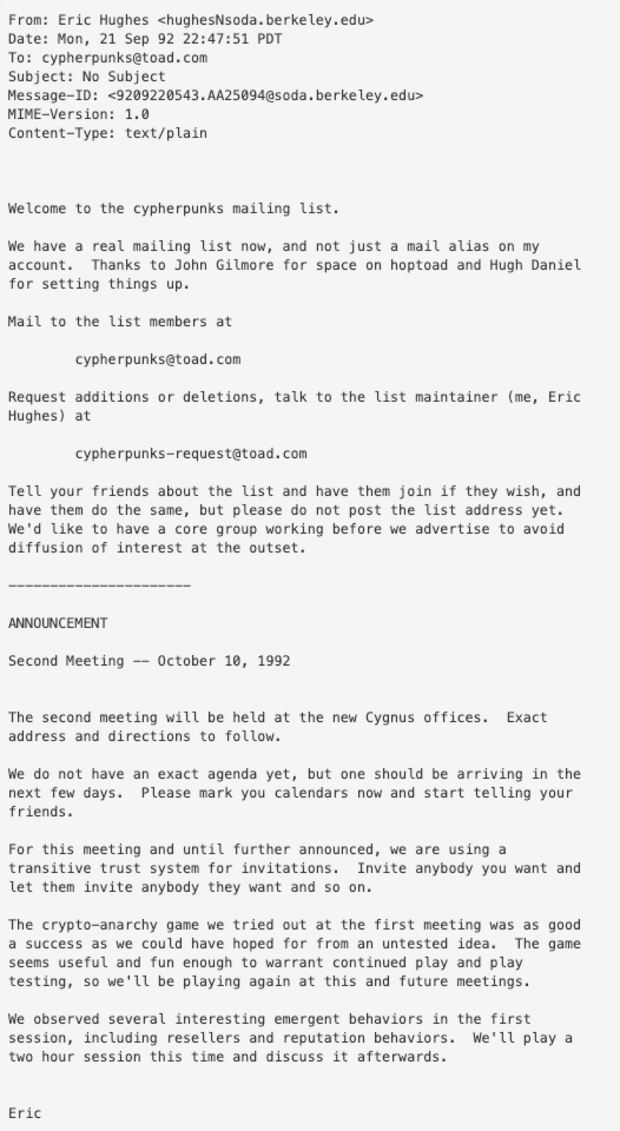

In 1992, one year after the public release of the world wide web, early Sun Microsystems employee John Gilmore, privacy activist Eric Hughes, and former Intel engineer Timothy May started to meet up in San Francisco to discuss how cryptography could be used to preserve freedom. That same year, they launched the Cypherpunks Mailing List (or “The List” for short), where the ideas behind Bitcoin were developed and eventually published by Nakamoto 16 years later.

On “The List,” cypherpunks like May wrote about how monarchies in the late Middle Ages were disrupted by the invention of the printing press, which democratized access to information. They debated how the creation of the open internet and cryptography could democratize privacy technology and disrupt the seemingly inevitable trend toward a global surveillance state.

Like many cypherpunks, Back’s college education was in computer science. But, serendipitously, he first studied economics between the ages of 16 and 18, and afterward, added a Ph.D. in distributed systems. If anyone was adequately trained to one day become a Bitcoin scientist, it was Back.

While he studied computer science in London in the early 1990s, he learned that one of his friends was working on speeding up computers to run faster encryption techniques. Through his friend, Back learned about the public-key encryption invented 15 years earlier by Diffie and Hellman.

Back thought this was a historic shift in the relationship between governments and individuals. Now citizens could communicate electronically in a way that no government could decrypt. He resolved to learn more, and his curiosity eventually led him to The List.

During the mid-1990s, Back was an avid participant on The List, which at its peak, was populated by dozens of new messages every day. By Back’s own account, he was the most active contributor at times, addicted to the cutting-edge conversations of the era.

Back was struck by how the cypherpunks wanted to change society by using code to peacefully create systems that could not be stopped. In 1993, Hughes wrote the movement’s seminal short essay, “A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto”:

“Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age. Privacy is not secrecy. A private matter is something one doesn’t want the whole world to know, but a secret matter is something one doesn’t want anybody to know. Privacy is the power to selectively reveal oneself to the world…

“…We cannot expect governments, corporations, or other large, faceless organizations to grant us privacy out of their beneficence. We must defend our own privacy if we expect to have any. We must come together and create systems, which allow anonymous transactions to take place. People have been defending their own privacy for centuries with whispers, darkness, envelopes, closed doors, secret handshakes, and couriers. The technologies of the past did not allow for strong privacy, but electronic technologies do.

“We the Cypherpunks are dedicated to building anonymous systems. We are defending our privacy with cryptography, with anonymous mail forwarding systems, with digital signatures, and with electronic money.

“Cypherpunks write code. We know that someone has to write software to defend privacy, and since we can’t get privacy unless we all do, we’re going to write it… Our code is free for all to use, worldwide. We don’t much care if you don’t approve of the software we write. We know that software can’t be destroyed and that a widely dispersed system can’t be shut down.”

This kind of thinking, Back thought, was what actually changes society. Sure, one could lobby or vote, but then society changes slowly, lagging behind government policy.

The other way, Back’s preferred strategy, was bold, permissionless change through inventing new technology. If he wanted change, he thought, he just had to make it happen.

III. The Crypto Wars

The original enemies of the cypherpunks were governments trying to stop citizens from using encryption. Back and friends thought that privacy was a human right. On the other hand, nation-states were petrified that citizens would create code allowing them to escape oversight and control.

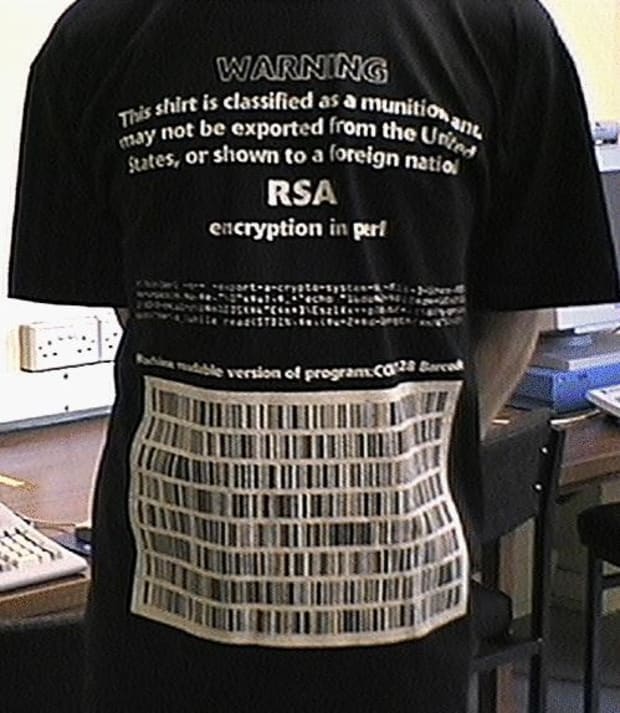

Authorities doubled down on old military standards — which classified cryptography alongside fighter jets and aircraft carriers as munitions — and tried to ban export of encryption software to kill its use globally. The aim was to scare people away from using privacy tech. The conflict became known as the “Crypto Wars,” and Back was a frontline soldier.

Back knew that the big picture effects of such a ban would cause many U.S. jobs to move offshore, and force vast amounts of sensitive information to remain unencrypted. But the Clinton Administration was not looking ahead, just at what was directly in front of it. And its biggest target was a computer scientist named Phil Zimmerman, who had in 1991 released the first consumer-level secret messaging system, called Pretty Good Privacy, or “PGP” for short.

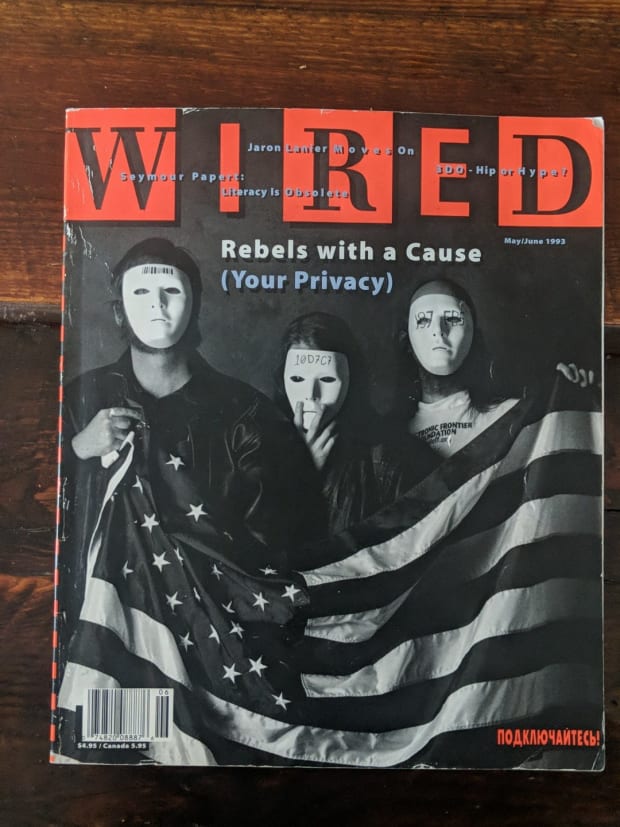

In the mid-1990s, WIRED covered the cypherpunks in a detailed profile:

PGP was an easy way for two individuals to communicate privately using PCs and the new world wide web. It promised to democratize encryption to millions of people and end the state’s decades-long control over private messaging.

As the face of the project, however, Zimmerman came under attack from corporations and governments. In 1977, three Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) scientists named Rivest, Shamir, and Adelman, implemented Diffie and Hellman’s ideas into an algorithm called RSA. MIT later issued a license for the patent to a businessman named Jim Bidzos and his company, RSA Data Security.

The cypherpunks were uneasy with such a vital toolkit being controlled by one entity, having a single point of failure, but all through the 1980s, licensing and fear of being sued had largely prevented them from releasing new programs based on the code.

At first, Zimmerman asked Bidzos for a free license for the software, but was denied. In defiance, Zimmerman released PGP as “guerilla freeware,” disseminating it through floppy disks and internet message boards. A young cypherpunk by the name of Hal Finney — who would later play a major role in the Bitcoin story — joined Zimmerman, helping to push the project forward. A 1994 WIRED feature hailed Zimmerman’s brazen release of PGP as a “pre-emptive strike against such an Orwellian future.”

Bidzos called Zimmerman a thief and mounted a campaign to halt the spread of PGP. Zimmerman eventually used a loophole to put out a new PGP version, which piggybacked on code that Bidzos had released for free, defusing the corporate threat.

But the federal government ultimately decided to investigate Zimmerman for exporting “munitions” under the Arms Control Export Act. In defense, Zimmerman argued that he was merely enacting his First Amendment rights of free speech by sharing open-source code.

At the time, the Clinton Administration argued that Americans had no right to encrypt. They pushed for legislation to force companies to install backdoors (“clipper chips”) into their equipment so that the State could have a skeleton key to any message these chips encrypted. Led by White House officials and congressmen like Joe Biden, they argued that cryptography would empower criminals, pedophiles and terrorists.

The cypherpunks rallied to support Zimmerman, who became a cause célèbre. They argued that anti-encryption laws were incompatible with U.S. traditions of free speech. The activists started to print the PGP source code in books and mail them overseas. Via the publishing of the code in printed form, Zimmerman and others theorized they could legally circumvent anti-munitions restrictions. Recipients would scan the code, reconstitute it, and run it, all to prove the point: you cannot stop us.

Back wrote short pieces of source code that any programmer could turn into a fully-functional privacy toolkit. Some activists tattooed snippets of this code on their bodies. Back famously started selling t-shirts with the code on the front and a piece of the U.S. Bill of Rights with “VOID” stamped over it on the back.

Activists finally sent a book containing the controversial code to the U.S. government’s Office of Munitions Control, asking if it could share it abroad. They never got a response. The cypherpunks guessed that the White House would never ban books, and in the end, they were right.

In 1996, the U.S. Department of Justice dropped its charges against Zimmerman. The pressure to force companies to use “clipper chips” subsided. Federal judges argued that encryption was a right protected by the First Amendment. Anti-cryptography standards were overturned, and encrypted messaging became a core part of the open web and e-commerce. PGP became “the most widely used email encryption software in the world.”

Today, companies and apps ranging from Amazon to WhatsApp and Facebook rely on encryption to secure payments and messages. Billions of people benefit. Code changed the world.

Back is self-deprecating and said that it is hard to say if his activism in particular made a difference. But certainly, the fight that the cypherpunks mounted was one of the main reasons that the U.S. government lost the Crypto Wars. The authorities tried to stop the code and failed.

This realization would loom large in Back’s mind 15 years later, in the summer of 2008, as he worked through that first email from Nakamoto.

IV. From DigiCash To Bit Gold

As the computing historian Stephen Levy said in 1993, the ultimate crypto tool would be “anonymous digital money.” Indeed, after winning the fight for private communications, the next challenge for the cypherpunks was to create digital cash.

Some cypherpunks were crypto-anarchists — deeply skeptical of the modern democratic state. Others believed it was possible to reform democracies to preserve individual rights. No matter what side they took, many considered digital cash to be the Holy Grail of the cypherpunk movement.

In the 1980s and 1990s, major steps were taken in the right direction, both culturally and technically, toward digital cash. From a cultural perspective, science fiction authors like Neal Stephenson captured the imagination of computer scientists around the world with depictions of future societies — where cash was gone — and different kinds of digital e-bucks were the currency du jour. At a time when credit cards and digital payments were already on the rise, there was a nostalgia for the privacy involved in making a cash payment, where the merchant does not know, store, or sell any information about the customer.

On the technical front, a cryptography scholar at the University of California, Berkeley named David Chaum took the powerful idea of public-key encryption and started to apply it to money.

In the early 1980s, Chaum invented blind signatures, a key innovation in the evolution of being able to prove ownership of a piece of data without revealing its provenance. In 1985, he published “Security Without Identification: Transaction Systems To Make Big Brother Obsolete,” a prescient paper that explored how the growth of the surveillance state could be slowed through private digital payments.

A few years later in 1989, Chaum and friends moved to Amsterdam, applied theory to practice, and launched DigiCash. The company aimed to allow users to convert euros and dollars into digital cash tokens. Bank credits could be turned into “eCash” and sent to friends outside of the banking system. They could store the new currency on their PC, for instance, or cash them out. The software’s strong encryption made it impossible for authorities to trace the money flow.

In a 1994 profile of DigiCash at its heyday, Chaum said that goal was to “catapult our currency system into the 21st century… in the process, shattering the Orwellian predictions of a Big Brother dystopia, replacing them with a world in which the ease of electronic transactions is combined with the elegant anonymity of paying in cash.”

Back said that cypherpunks like him were initially excited about eCash. It prevented outside observers from knowing who had sent how much to whom. And the tokens resembled cash in as much as they were bearer instruments that users controlled.

Chaum’s personal philosophy also resonated with the cypherpunks. In 1992, he wrote that mankind was at a decision point, where “in one direction lies unprecedented scrutiny and control of people’s lives; in the other, secure parity between individuals and organizations. The shape of society in the next century,” he wrote, “may depend on which approach predominates.”

DigiCash, however, failed to get the right funding, and later that decade went bankrupt. For Back and others, this was a big lesson: digital cash needed to be decentralized, without a single point of failure.

Back had personally gone to great lengths to preserve privacy in society. He once ran a “mixmaster” service to help people keep their communications private. He would accept incoming email and forward it along in a way that was not traceable. To make it hard to figure out that he was running the service, Back rented a server from a friend in Switzerland. To pay him from London, he would mail physical cash. Eventually, the Swiss Federal Police showed up at his friend’s office. The next day, Back shut down his mixer. But the dream of digital cash kept burning in his mind.

Centralized digital money could fail operationally, come under regulatory capture, or go bankrupt, à la DigiCash. But its biggest vulnerability is monetary issuance dictated by a trusted third party.

On March 28, 1997, after years of reflection and experimentation, Back invented and announced Hashcash, an anti-spam concept later cited in Nakamoto’s white paper that would prove foundational for Bitcoin mining. Hashcash would eventually enable financial “proof of work”: a currency that needed the expenditure of energy to produce new monetary units, thus making money harder and fairer.

Governments historically have frequently abused their monopolies on the issuance of money. Tragic examples include ancient Rome, Weimar Germany, Soviet Hungary, the Balkans in the 1990s, Mugabe’s Zimbabwe, and the 1.3 billion people today living under double, triple, or quadruple digit inflation everywhere from Sudan to Venezuela.

Against this backdrop, cypherpunk Robert Hettinga wrote in 1998 that properly decentralized digital cash would mean that economics would no longer have to be “the handmaiden of politics.” No more making new huge amounts of new cash with the click of a button.

One vulnerability of Hashcash was that if someone tried to design a currency with its anti-spam mechanism, users with faster computers could still cause hyperinflation. A decade later, Nakamoto would solve this issue with a key innovation in Bitcoin called the “difficulty algorithm,” where the network would reset the difficulty of minting coins every two weeks based on the total amount of power spent by the users on the network.

In 1998, the computer engineer Wei Dai released his b-money concept. B-money was “an anonymous, distributed electronic cash system,” and it proposed a “scheme for a group of untraceable digital pseudonyms to pay each other with money and to enforce contracts amongst themselves without outside help.”

Dai was inspired by Back’s work with Hashcash, incorporating proof of work into b-money’s designs. While the system was limited and turned out to be impractical, Dai left behind a series of writings that echoed Hughes, Back, and others.

In February 1995, Dai sent an email to The List, making a case for technology, not regulation, as the savior of our future digital rights:

“There has never been a government that didn’t sooner or later try to reduce the freedom of its subjects and gain more control over them, and there probably never will be one. Therefore, instead of trying to convince our current government not to try, we’ll develop the technology… that will make it impossible for the government to succeed.

“Efforts to influence the government (e.g., lobbying and propaganda) are important only in so far as to delay its attempted crackdown long enough for the technology to mature and come into wide use.

“But even if you do not believe the above is true, think about it this way: If you have a certain amount of time to spend on advancing the cause of greater personal privacy (or freedom, or cryptoanarchy, or whatever), can you do it better by using the time to learn about cryptography and develop the tools to protect privacy, or by convincing your government not to invade your privacy?”

That same year, in 1998, an American cryptographer named Nick Szabo proposed bit gold. Building off of the ideas of other cypherpunks, Szabo proposed a parallel financial structure whose token would have its own value proposition, separate from the dollar or the euro. Having worked at DigiCash, and seen the vulnerabilities of a centralized mint, he thought gold was a worthwhile asset to try to replicate in the digital space.

Bit gold was important because it finally linked the ideas of monetary reform and hard money to the cypherpunk movement. It tried to make the “provable costliness” feature of gold digital. A gold necklace, for example, proves that the owner either expended significant time and energy and resources to dig that gold out of the ground and make it into jewelry, or paid a lot of money to buy it. Szabo wanted to bring provable costliness online. Bit gold was never implemented, but it continued to inspire the cypherpunks.

The next few years saw the rise of e-commerce, the dot-com bubble, and then the emergence of today’s internet mega-corporations. It was a busy and explosive time online. But there was not another major advancement in digital cash for five years. This points to the fact that first, there were not many people working on this idea, and second, making it all work was extraordinarily challenging.

In 2004, former PGP contributor Finney finally announced reusable proof of work, or “RPOW” for short. This was the next major innovation in the path toward Bitcoin.

RPOW took the idea of bit gold and added a network of open-source servers to verify transactions. One could attach some bit gold to an email, for example, and the recipient would acquire a bearer asset with provable costliness.

While Finney launched RPOW in a centralized fashion on his own server, he had plans to eventually decentralize the architecture. These were all key steps toward Bitcoin’s foundation, but a few more puzzle pieces still needed to slide into place.

V. Running Bitcoin

In 1999, Back finished his Ph.D. in distributed systems and began work in Canada for a company called Credentica. There, he helped build the Freedom Network, a tool that allowed individuals to browse the web privately. Back and his colleagues used what are known as “zero-knowledge proofs” (based on Chaum’s blind signatures) to encrypt communications over this network, and sold access to the service.

Back, as it turns out, was also ahead of his time on this key innovation. In 2002, computer scientists improved on Credentica’s model by taking a U.S. government private web browsing project called “onion routing” open source. They called it the Tor Network, and it inspired the age of the virtual-private networks (VPNs). It remains the gold standard for private web browsing today.

In the early and mid-2000s, Back finished his work at Credentica, was recruited by Microsoft for a short stint as a cybersecurity researcher, and then joined a new startup doing peer-to-peer encrypted collaboration software. All the while, Back kept the idea of digital cash in the back of his mind.

When the email from Nakamoto arrived in August 2008, Back was intrigued. He read it carefully and responded, suggesting that Nakamoto look into a few other digital money systems, including Dai’s b-money.

On October 31, 2008, Nakamoto published the Bitcoin white paper on The List. The first sentence promised the dream that so many had chased: “a purely peer-to-peer version of electronic cash would allow online payments to be sent directly from one party to another without going through a financial institution.” Back’s Hashcash, Dai’s b-money, and earlier cryptography research were all cited.

As digital cash historian Aaron van Wirdum wrote, “in Bitcoin, Hashcash killed two birds with one stone. It solved the double-spending problem in a decentralized way, while providing a trick to get new coins into circulation with no centralized issuer.” He noted that Back’s Hashcash was not the first ecash system, but a decentralized electronic cash system “might have been impossible without it.”

On January 9, 2009, Nakamoto launched the first version of the Bitcoin software. Finney was one of the first to download the program and experiment with it, as he was excited that someone had continued his work from RPOW.

On January 10, Finney posted the famous tweet: “Running bitcoin.” The peaceful revolution had begun.

VI. The Genesis Block

In February 2009, Nakamoto summarized the ideas behind Bitcoin on a peer-to-peer tech community message board:

“Before strong encryption, users had to rely on password protection to keep their information private. Privacy could always be overridden by the admin based on his judgement call weighing the principle of privacy against other concerns, or at the behest of his superiors. Then strong encryption became available to the masses, and trust was no longer required. Data could be secured in a way that was physically impossible for others to access, no matter what reason, no matter how good the excuse, no matter what.

“It’s time we had the same thing for money. With e-currency based on cryptographic proof, without the need to trust a third-party middleman, money can be secure and transactions effortless. One of the fundamental building blocks for such a system is digital signatures. A digital coin contains the public key of its owner. To transfer it, the owner signs the coin together with the public key of the next owner. Anyone can check the signatures to verify the chain of ownership. It works well to secure ownership, but leaves one big problem unsolved: double-spending. Any owner could try to re-spend an already spent coin by signing it to another owner. The usual solution is for a trusted company with a central database to check for double-spending, but that just gets back to the trust model. In its central position, the company can override the users…

“Bitcoin’s solution is to use a peer-to-peer network to check for double-spending… The result is a distributed system with no single point of failure. Users hold the crypto keys to their own money and transact with each other, with the help of the P2P network to check for double-spending.”

Nakamoto had stood on the shoulders of Diffie, Chaum, Back, Dai, Szabo, and Finney and forged decentralized digital cash.

The key, in retrospect, was to combine the ability to make private transactions outside of the banking system with the ability to hold an asset that could not be debased via political interference.

This last feature was not top of mind for the cypherpunks before the late 1990s. Szabo had certainly aimed for it with bit gold, and others inspired by Austrian economists like Fredrich Hayek and Murray Rothbard had long discussed getting the creation of money out of government hands. Still, generally, cypherpunks had prioritized privacy over monetary policy in early visions of digital cash.

The ambivalence towards monetary policy shown by privacy advocates is still evident today. Many left-leaning civil liberties groups that have protected American digital rights over the past two decades have either ignored or been outright hostile to Bitcoin. The 21 million-coin limit, scarcity, and “hard money” qualities proved foundational to achieving privacy through digital cash. Yet, digital rights advocacy groups have largely not recognized nor celebrated the role that proof of work and an unchanging monetary policy can play in protecting human rights.

To underline the primary importance of scarcity and predictable monetary issuance in the making of digital cash, Nakamoto released Bitcoin not after a government surveillance scandal, but in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis and ensuing money printing experiments of 2007 and 2008.

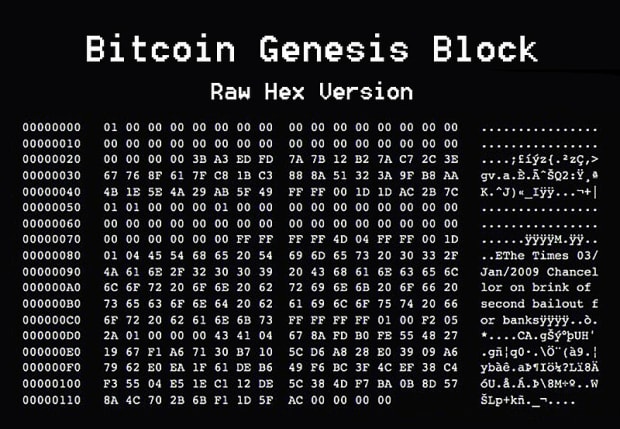

The first record in Bitcoin’s blockchain is known as the Genesis Block, and it is a political rallying cry. Right there in the code is a message worth pondering: “The Times / 03 Jan / 2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.”

The message refers to a headline in The Times of London, describing how the British government was in the process of bailing out a failing private sector through increasing both sides of its balance sheet. This was part of a broader global movement where central banks created cash for commercial banks out of thin air, and in return acquired assets ranging from mortgage-backed securities to corporate and sovereign debt. In the U.K., the Bank of England was printing more money to try to save the economy.

Nakamoto’s Genesis statement was a challenge to the moral hazard created by the Bank of England, which was functioning as a lender of last resort for British companies that had followed reckless policies and were now in danger of going bankrupt.

The average Londoner would be the one to pay the price during a recession, whereas the Canary Wharf elite would find ways to protect their wealth. No British bankers would go to prison during the Great Financial Crisis, but millions of lower- and middle-class British citizens suffered. Bitcoin was more than just digital cash, it was an alternative to central banking.

Nakamoto did not think highly of the model of bureaucrats increasing debt to save ever-more financialized economies. As they wrote:

“The root problem with conventional currency is all the trust that’s required to make it work. The central bank must be trusted not to debase the currency, but the history of fiat currencies is full of breaches of that trust. Banks must be trusted to hold our money and transfer it electronically, but they lend it out in waves of credit bubbles with barely a fraction in reserve.”

Nakamoto launched the Bitcoin network as a competitor to central banks, offering the automation of monetary policy and eliminating the smoky back rooms where small handfuls of elites would make decisions about public money for everyone else.

VII. An Engineering Marvel

Initially, Back was impressed by Bitcoin. He read a technical field report that Finney published in early 2009 and realized Nakamoto had solved many of the problems that had previously prevented the creation of an effective digital cash. What perhaps impressed Back most, and made the Bitcoin project stronger than any he had ever seen, was that sometime in early 2011, Nakamoto vanished forever.

In 2009 and 2010, Nakamoto posted updates, discussed tweaks and improvements to Bitcoin, and shared their thoughts on the future of the network, mainly on an online forum called Bitcointalk. Then, one day, they disappeared, and have never been conclusively heard from since.

At the time, Bitcoin was still a nascent project, and Nakamoto was still conceivably a central point of failure. In late 2010, they were still acting as a benevolent dictator. But by removing themselves — and giving up a lifetime of fame, fortune, and awards — they made it impossible for governments to be able to damage the network by arresting or manipulating its creator.

Before leaving, Nakamoto wrote:

“A lot of people automatically dismiss e-currency as a lost cause because of all the companies that failed since the 1990s. I hope it’s obvious it was only the centrally controlled nature of those systems that doomed them. I think this is the first time we’re trying a decentralized, non-trust based system.”

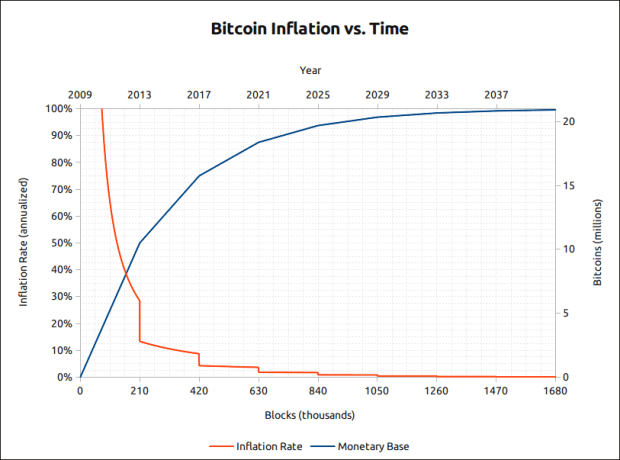

Back agreed. Beyond being struck by the way Nakamoto revealed Bitcoin and then disappeared, he was especially intrigued by Bitcoin’s monetary policy, which was programmed to issue a smaller and smaller amount of coins each year until the 2130s, when the last bitcoin would be released and no further bitcoin would be issued. The total number of coins was set in stone at just shy of 21 million.

Every four years, the new Bitcoin provided to winning miners as part of the block reward would be cut in half, in an event now celebrated as the “halving.”

When Nakamoto was mining bitcoin in early 2009, the subsidy was 50 bitcoin. The subsidy dropped to 25 in 2012, 12.5 in 2016, and 6.25 in April 2020. As of late 2021, nearly 19 million bitcoin have been mined, and by 2035, 99% of all bitcoin will be distributed.

The remainder will be distributed over the following century, as a lingering incentive to miners, who over time must shift to making their profit from transaction fees instead of the ever-shrinking subsidy.

Even in 2009, Nakamoto, Finney, and others speculated that Bitcoin’s unique “hard-capped” monetary policy with a limit of 21 million total coins could make the currency extremely valuable if it one day took off.

In addition to the innovative monetary policy, Back thought the so-called “difficulty algorithm” was also a significant scientific breakthrough. This trick addressed a concern Back had originally had for Hashcash, where users with faster computers could overwhelm the system. In Bitcoin, Nakamoto prevented this from happening by programming the network to reset the difficulty required to successfully mine a block every two weeks, based on how long mining the last two weeks took.

If the market crashed, or some catastrophic event happened (for example, when the Chinese Communist Party kicked half the world’s Bitcoin miners offline in May 2021), and the total global amount of energy spent mining Bitcoin (the “hash rate”) went down, it would take longer than normal to mine blocks.

However, with the difficulty algorithm, the network would shortly compensate, and make mining easier. Conversely, if the global hash rate went up, perhaps if a more efficient piece of equipment were invented, and miners found blocks too quickly, the difficulty algorithm would shortly compensate. This seemingly-simple feature gave Bitcoin resilience and has helped it survive massive seasonal mining turmoil, precipitous price crashes, and regulatory threats. Today, Bitcoin’s mining infrastructure is more decentralized than ever.

These innovations made Back think that Bitcoin could potentially succeed where other digital currency attempts had failed. However, one glaring problem remained: Bitcoin was not very private.

VIII. Bitcoin’s Privacy Problem

For the cypherpunks, privacy was a key goal. Previous iterations of e-cash, like the one produced by DigiCash, had even made the tradeoff of achieving privacy by sacrificing decentralization. There could be immense privacy in these systems, but users had to trust the mint and were at risk of censorship and devaluation.

In creating an alternative to the mint, Nakamoto was forced to rely on an open ledger system, where anyone could publicly view all transactions. It was the only way to ensure auditability, but it sacrificed privacy. Back says that he still thinks this was the right engineering decision.

There had been more work done in the area of private digital currencies since DigiCash. In 1999, security researchers published a paper called “Auditable Anonymous Electronic Cash,” around the idea of using zero-knowledge proofs. More than a decade later, the “Zerocoin” paper was published as an optimization of this concept. But to try to achieve perfect privacy, these systems made tradeoffs.

The math required for these anonymous transactions was so complicated that it made each transaction very large and each spend very time-consuming. One reason Bitcoin works so well today is that the average transaction is just a couple of hundred bytes. Anyone can cheaply run a full node at home and keep track of Bitcoin’s history and incoming transactions, keeping power over the system in the hands of users. The system does not rely on a few supercomputers. Rather, regular computers can store the Bitcoin blockchain and transmit transaction data at low cost because data use is kept to a minimum.

If Nakamoto had used a Zerocoin-type model, each transaction would have been more than 100 kilobytes, the ledger would have grown huge, and only a handful of people with specialized datacenter equipment could have run a full node, introducing the possibility for collusion, censorship, or even a small group of people deciding to increase the monetary supply beyond 21 million. As the Bitcoin community mantra asserts, “don’t trust, verify.”

Back said that he is, in retrospect, glad that he did not mention the 1999 paper to Nakamoto in his emails. Creating decentralized digital cash was the most crucial part: privacy, he thought, could be programmed in later.

By 2013, Back decided Bitcoin had demonstrated enough stability to be the foundation for digital cash. He realized he could take some of his applied cryptography experience and help make it more private. Around this time, Back started spending 12 hours a day reading about Bitcoin. He said that he lost track of time, barely ate, and barely slept. He was obsessed.

That year, Back suggested a few key ideas to the Bitcoin developer community on channels like IRC and Bitcointalk. One was changing the type of digital signature that Bitcoin uses from ECDSA to Schnorr. Nakamoto did not use Schnorr in the original design, despite the fact that it offered better flexibility and privacy for users, because it had a patent on it. But that patent had expired.

Today, Back’s suggestion is being implemented, as Schnorr signatures are being added to the Bitcoin network next month as part of the Taproot upgrade. Once Taproot is activated and used at scale, most types of wallets and transactions will look the same to observers (including governments), helping to fight the surveillance machine.

IV. Confidential Transactions

Back’s biggest vision for Bitcoin was something called Confidential Transactions. Currently, a user exposes the amount of bitcoin they send with each transaction. This enables auditability of the system — everyone at home running the Bitcoin software can ensure that there are only a certain number of coins — but it also enables surveillance to happen on the blockchain.

If a government can pair a Bitcoin address with a real-world identity, they can follow the funds. Confidential Transactions (CT) would hide the transaction amount, making surveillance much more difficult or perhaps even impossible when used in conjunction with CoinJoin techniques.

In 2013, Back talked to a handful of core developers — the “Bitcoin Wizards,” as he calls them — and realized it would be extremely difficult to implement CT, as the community understandably prioritized security and audibility over privacy.

Back also realized that Bitcoin was not very modular — meaning one could not experiment with CT inside the system — so he helped come up with the idea of a new kind of experimental testbed for Bitcoin technology, so that he could test out ideas like CT without harming the network.

Back quickly realized that this would be a lot of work. He would have to build software libraries, integrate wallets, get compatibility with exchanges, and create a user-friendly interface. Back convinced a Silicon Valley venture capitalist to give him $500,000 to try to build a company to make it all happen.

With seed funding in hand, Back teamed up with noted Bitcoin Core developer Greg Maxwell and investor Austin Hill and launched Blockstream, which is today one of the world’s biggest Bitcoin companies. Back remains CEO, and pursues projects like Blockstream Satellite, which enables Bitcoin users around the world to use the network without needing internet access.

In 2015, Back and Maxwell released a version of the Bitcoin “testnet” they had envisioned and called it Elements. They proceeded to enable CT on this sidechain — now called Liquid — where today hundreds of millions of dollars are settled privately.

Bitcoin users fought what is known as the “Blocksize War” against big miners and corporations between 2015 and 2017 to keep the blocksize reasonably limited (it did increase to a new theoretical maximum of 4 megabytes) and keep power in the hands of individuals, so any plan to significantly increase the size of blocks in the future could be met with stiff resistance.

Back still thinks it is possible to optimize the code and get CT transactions small enough to implement in Bitcoin. It is still several years away, at best, from being added, but Back continues on his quest.

For now, Bitcoin users can improve their privacy through techniques like CoinJoin, CoinSwap, and by using second-layer technology like the Lightning Network or sidechains like Mercury or Liquid.

In particular, Lightning — another area where Back’s team at Blockstream invests heavily through work on c-lightning — helps users spend bitcoin more cheaply, quickly, and privately. Through innovations like this, Bitcoin serves as censorship-resistant and debasement-proof savings tech for tens of millions of people around the world, and is becoming more friendly for daily transactions.

In the near future, Bitcoin could very well fulfill the cypherpunk vision of teleportable digital cash, with all of the privacy aspects of cash and all of the store-of-value ability of gold. This could prove one of the most important missions of the coming century, as governments experiment with and begin to introduce central bank digital currencies (CBDCs).

CBDCs aim to replace paper money with electronic credits that can be easily surveilled, confiscated, auto-taxed, and debased via negative interest rates. They pave the way for social engineering, pinpoint censorship and deplatforming, and expiration dates on money.

But if the vision for Bitcoin’s digital cash can be fully achieved, then in Nakamoto’s words, “we can win a major battle in the arms race and gain a new territory of freedom for several years.”

This is the cypherpunk dream, and Adam Back is focused on making it happen.

This is a guest post by Alex Gladstein. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.