- December 16, 2021

- Posted by: admin

- Category: BitCoin, Blockchain, Cryptocurrency, Investments

An economic system built upon a decentralized time stamp server does more than just solve the double spend, it commodifies time itself.

I had a long drive ahead of me. Nine hours down the coast, with a few stretches of time I knew I’d be out of streaming service range, and perhaps even out of AM/FM. Knowing this, I took a moment and dropped by my local Goodwill to take a gander at their CD collection before making my way. Lo and behold, I found a 3-CD boxed set of a Grateful Dead show from the 70s I had loved as a teenager, and figured that was the best bang for my couple of bucks: nearly three hours of guitars, feedback, percussive clomping and pitchy-sometimes-but-earnest-at-all-times singing. I bet the overlap of Bitcoiners and Dead Heads is slim, and I am not nearly as evangelical about the Dead’s underlying fundamentals, but alas, as I drove further into the cosmic slop, a parallel between the two movements formed. As the hours flew by, I couldn’t help but think how Bitcoin not only will bring about a global and free energy market, but with it, the re-commodification of time.

There’s a lot of talk about time in the Bitcoin space, and for good reason. A fundamental mechanic of the solution to the Byzantine Generals’ problem is the immutability of the timestamp that orders all Bitcoin transactions. Without this component, the capped supply issuance that ensures digital scarcity would be meaningless; it doesn’t matter how little bitcoin exists if one can just double-spend the same UTXO at a whim.

Proof-of-work creates immutable, decentralized truth by necessitating not just energy, but also the time spent searching for nonces for output hashes with enough leading zeroes to bring the next block header below the current difficulty target. Bitcoin does a brilliant job of utilizing the standardized local clock of a processor on the network to find an average of time spent (600 seconds target per block) across the whole network without relying on a centralized clock source to validate transaction orders. People like to scoff at Bitcoin transactions being inefficient, or slow, without realizing the implications of a global, digitally scarce, permission-less bearer asset with immutable, final settlement in under 30 minutes. The blockchain is simply a database of transactional signatures crystalized in impunity via a continuous hash string of blockheaders hashed with candidate block transactions in order to find the next blockheader. By stacking the previous blocks output hash on top of a universal forgetful function to find the next nonce, the serpentine chain of ledger becomes ever immutable; as every block stacks alongside the upward difficulty adjustment continuing its decade ascent, it becomes harder, and importantly, more wasteful for a bad faith actor to try and reorganize spends.

The act of spending electrical energy is not enough to find value in the digital space, it must be applied directly to spending time effectively, accurately computing within the consensus and thus securing the Bitcoin blockchain.

The Grateful Dead weren’t always known by that name, and in fact, they got their first public audiences performing under the name “The Warlocks.” Unbeknownst to each other at the time, they shared that name with a young, upstart art band out of New York City. When the slow and lossy communications reached their respective coast via the new, blossoming independent music scene, they both decided to change their name. The Dead went on to see fairly imminent success throughout the following decades, whilst their counterparts changed their name to The Velvet Underground and enjoyed somewhat critical but overall muted popularity until a resurgence of their canon in the late 70s. Neither one of them wanted to spend the time to make a claim to their brand, and thus both moved on without so much any litigation or litigators. The Dead did a lot of things that are unheard of today in the hyper-commodification era of art, but perhaps none more important than allowing technologicly-savvy fans to bring their own recording equipment into their venues and tape the improvisation-heavy performances for their own, non-commercial use. A devoted taping community grew out of this allowance, and an entirely new way for hungry fans to engage with the product gave rise to a peer-to-peer market of tapes of shows highlighted for a spattering of personal reasons; someone’s one-hundredth show, a birthday, New Year’s Eve, debut of new material, a particularly good version of a beloved song, etc. Over time, this strictly-non-commercially-incentivized community drove each other to higher heights of recording quality, with new masters, new techniques, better microphones and better gear led to a powerful, decentralized taper community ready to offer their celluloid of choice for yours in a free market of experiences.

The particular boxed set I bought is from a series called Dick’s Picks, named after the long time soundboard engineer of the band who utilized the data harvested from decades of trade and discussion amongst diehards to find the overwhelming favored shows of interest and, pulling from the archives of recordings directly from the band’s own board, released commercial products of high quality directly targeted at the fans who made those shows famous in the first place by taping and trading their experience. I was a couple hours into my drive, stopping to feel the pain of filling my car with gas, when I decided to humor myself and see what these things sell for; it seemed kind of strange, knowing that nearly every show the band has ever played at this point has been recorded, located, and tagged online, legally, and for free, that these box sets could ever retain their value, furthermore proved by the fact I had found one for only a few dollars.

Imagine my initial confusion when I found that not only did they retain their value, the three discs were listed on eBay anywhere from $65-$150, appreciating at least three times in value since the February 1996 release. So not only did they compete with the slightly lower quality but freely distributed tapes, but by printing a limited run, they created supply less than ultimate demand. Had the person that donated this set to Goodwill taken the time to see its value on the open market, they might have made a different decision. Had an employee of Goodwill taken the time to search reseller markets, they might have priced the set with a higher premium.

The point isn’t about whether these discs kept pace with gold from 1996 to 2021, but how they leveraged an open market of experiences to be commodified without innate commercial intent. The band put their advertising and commercial outreach into the hands of those that understood the product the best, resulting in deeper bond between the perceived value of the experience through the network of audience and the value of a high-fidelity commodity for re-experience. Certain nights, the group consciousness of a tuned-in-but-definitely-dropped-out masses, on the stage and off, came together in just the right way; those were the nights you wanted to play in your van on your four-and-a-half hour drive to the next night’s show.

A whole community of trading tapes grew alongside the formidable touring empire of the band’s now ubiquitous pop-culture presence. They always sold plenty of tickets, plenty of albums, plenty of t-shirts, and whatever loss of property they seemingly endured by allowing their fans this freedom was more than made up in other revenue streams. But beyond the obvious free marketing, production, and distribution, the band got something far more meaningful; they got a large following of humans to experience their lives listening to the recordings of the group. I don’t care to convince you on their merits, that is not the point here, but I think anyone should agree there is simply something different about the way fans of this group behave in a lifestyle manner. This open network, completely symbiotic to the band’s own commercial success, allowed a mutually perceived experience to be commodified and thus socially valued. The audience grew itself, and soon enough the market demanded less tape hiss and the more balanced highs of the eventually-released official discs.

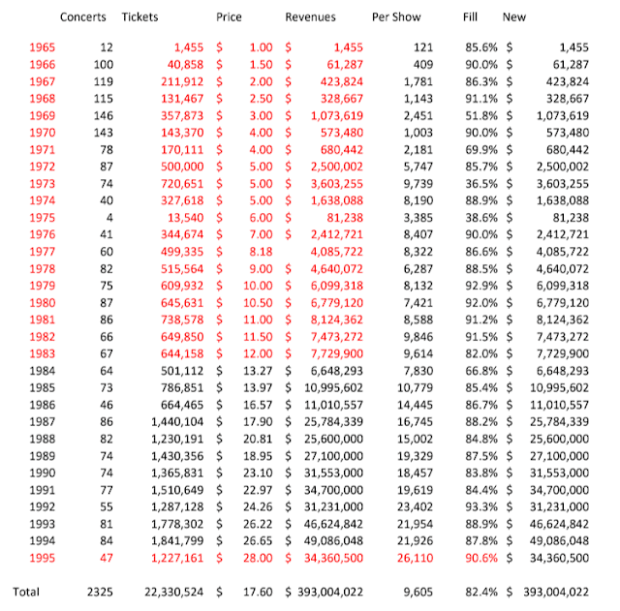

One of the reasons those that did could even afford to drop out of the working class to abscond upon the concrete ribbons was sounder money. In fact, this particular night I happened on was recorded in winter 1970, before Nixon even took us off the gold standard. It took a minimum-wage worker less than a shift to afford the $4 ticket, and gas had not yet begun its rise from half a dollar in 1972 to a $1.35 in 1981. It didn’t take a lot of time to earn enough for a three-show run, and hundreds of fans modeled lifestyle-supporting revenue streams around the nomadic culture; large craft bazaars would pop up in the parking lots with kitchens, arts and of course tape exchanges for those that missed a show to get up to date.

For many, the Grateful Dead were more than just a hobby, it was their life and livelihood. The lifestyle required such minimal overhead and the dollar was strong enough that the momentum of the summer of love spilled out into the hopeful halls and amphitheaters across the nation. The purchasing power of your time spent in labor was strong against the cheap price of goods and services; your time was worth something. As we find ourselves in an inflating goods and service market (in part) due to an expanding monetary supply, we find our time being devalued below our ability to keep the pace with rising prices. We work more and more and get less and less for it. This is a problem that can be solved (in part) with a technological upgrade to our monetary network. By imbuing our time laboring into a disinflationary and decentralized economic protocol, instead of fighting a compounding, hopeless struggle against the leaking entropy from an inflating dollar system, humans can spend more time making beautiful things for themselves and others. Bitcoin’s dollar-denominated purchasing power does not rely on the dollar inflating more than the 2% target per year since the third halving algorithmically brought the relative-to-total supply issuance below 1.8%. Imagine a free, global market represented with a deflationary supply backed by geographically-independent, universally permissionless energy sources spending their time carving a hash string of blocks to communicate immutable transactional history through a network of peer-to-peer participants. There are very, very few use cases for a blockchain that would not be better served with a faster, more centralized database, but the historic ledger of volatility between human energy and capital is certainly at a level of demanding such necessity.

The history of humanity deserves a decentralized, open and yet immutable level of trust. Proof-of-work is not just the answer to the Byzantine General’s problem, it is also the first empirically sound answer to communally experienced time, and with it brings the assurance and ability for users to trust the commodity of time that is Bitcoin in the future. Bitcoin does change time preference in a literal time mechanism, for proof-of-work is a proof of history of spent computational power. It is a clock, just not a predictive clock. Mostly rubbish for planning future events, but in actuality it is an immutably true and decentralized standard of history and time; a decentralized time stamp server in order to solve the digital double-spend problem. Every payment a Bitcoin user receives of this digitally scarce bearer asset gets more purchasing power over time, and thus your economic incentive is to conserve your satoshis to maximize economic “yield.”

In these use cases, you can see the “time preference” variable changing directly alongside the economic incentive of the protocol. But when did this new standard of history go from being simply a shared database amongst cypherpunks to the immutable ledger of truth we all know today? I would argue it happened just before December 2012, as the nodes enforced the first halving upon the miners, just a few weeks before the astrological calendar of the Mayans ended. The implications that a new standard of time could have on human experience are vast. The path of a group society was incredibly modified with the mechanisms and technological advancements that allowed us to have a group consensus on months, days, hours, minutes and others. Through so-called quantum experiments such as the double-slit experiment, humans have in fact been able to see the modulation of wave forms of propelled atoms depending on the standard of time selected in the data harvesting. Perhaps we could recreate the experiment by taking snapshots each time a block is mined to look for demonstrative effects of a new standard of passing time in the observable universe. But regardless of what unknown implications of empirical, decentralized truth may come in the physics world, the way humans interact with time on a Bitcoin standard is quite different than how we used to on a fiat standard. You could make enough for a Dead ticket, the gas to get there, and a place to stay in a day of minimum wage work in 1970. This allowed more resources to be spent on capturing the shows in higher fidelity, and an abundance of human time to create a prolific culture around the group. The open-source community around Bitcoin makes it better, stronger and more available to serve more humans, but this social construct would not have coalesced around the protocol without the deflationary effects of the commodification of time via Bitcoin. You can save yourself a lot of time by using Bitcoin to save yourself a lot of time.

This is a guest post by Mark Goodwin. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC, Inc. or Bitcoin Magazine.