- February 24, 2022

- Posted by: admin

- Category: BitCoin, Blockchain, Cryptocurrency, Investments

How is Bitcoin defended by energy? And what is a nonce? These questions and more are answered within!

How mining works is fascinating. When I explain it to people, I enjoy seeing their face the moment their mind is blown. I’ll explain it here, but just know, I’m imagining all your faces as your minds blow!

I have to start with hash functions. Without hash functions, Bitcoin would not be possible. Let me explain what they are first, not only so you can sound cool at parties, but also because it’s fundamental to understanding how Bitcoin works — particularly mining but also transactions — under the hood.

You don’t need to understand how Bitcoin works in order to benefit from it, just like how you don’t need to understand how TCP/IP works to use the internet. But do go on, because it’s quite interesting and I’ll make it easy to understand, I promise.

Hash Functions

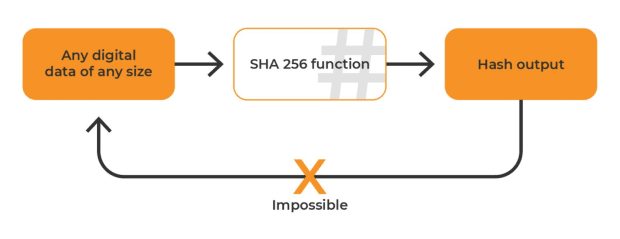

Let’s start with a schematic which I’ll explain below…

On the left is the input, the center is the function, and on the right is the output. The input can be any data, as long as it’s digital. It can be of any size, provided your computer can handle it. The data is passed to the SHA256 function. The function takes the data and calculates a random-looking number, but with special properties (discussed later).

The first Secure Hash Algorithm (SHA) was originally developed by the NSA and there are many different versions now (Bitcoin uses SHA256). It’s a set of instructions for how to jumble up the data in a very complicated but specified way. The instructions are not a secret and it’s even possible to do it by hand, but it is very tedious.

For SHA256, the output is a 256-bit number (not a coincidence).

A 256-bit number means a binary number 256 digits long. Binary means the value is represented with two symbols, either 0 or 1. Binary numbers can be converted to any other format, for example decimal numbers, which are what we are familiar with.

Although the function returns a 256-digit binary number, the value is usually expressed in hexadecimal format, 64 digits long.

Hexadecimal means that instead of 10 possible symbols like we are used to with decimal (0 to 9), we have 16 symbols (The ten we are used to, 0-9, plus the letters a, b, c, d, e, and f; which have the values 11 to 15). As an example, to represent the value of decimal 15 in hexadecimal, we just write “f” and it’s the same value. There’s plenty of information available online with a quick Google search if you need more elaboration.

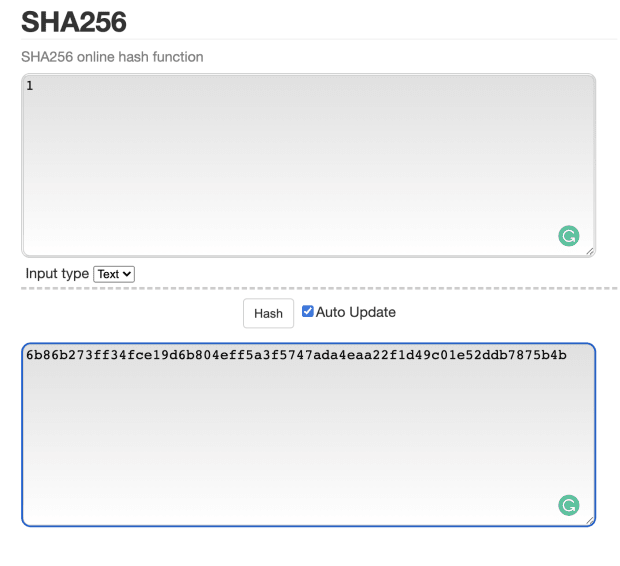

To demonstrate SHA256 in action, I can take the number 1 and run it through an online hash calculator, and got this output (in hexadecimal):

The top box is the input, the bottom box is the resulting output.

Note that all computers in the world will produce the same output, provided the input is the same and the SHA256 function is used.

The hexadecimal number output, if converted to decimal, is (notice it takes more digits to write):

48,635,463,943,209,834,798,109,814,161,294,753,926,839,975,257,569,795,305,637,098,542,720,658,922,315

And converted to binary it is:

11010111000011010110010011100111111111100110100111111001110000110011101011010111000000001001110111111110101101000111111010101110100011110101101101001001110101010100010001011110001110101001001110000000001111001010010110111011011011110000111010110110100101111010111001101011100110101110011010111001101011100110101110011010111001101011100111

Just out of interest, here is the same value in base 64.

1w1k5/5p+cM61wCd/rR+ro9bSdVEXjqTgDylu28OtpY=

Note that the smallest possible value SHA256 could return is zero, but the LENGTH is still 256 bits. This is how zero is represented:

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

And the largest possible value is:

1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111

In decimal, that’s:

115,792,089,237,316,195,423,570,985,008,687,907,853,269,984,665,640,564,039,457,584,007,913,129,639,935

In hexadecimal, it is:

FFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF

Note there are exactly 64 F’s.

Zero in hexadecimal can simply be written as one single zero, but for hash output, it’s 64 of them to keep to the requirement of a fixed size output:

0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Here is a summary of some facts about the hash function that are vital to appreciate:

- The input cannot be determined from the output

- The input can be any length

- The output is always the same length

- The output will always be reproduced identically if you provide the same input.

- Any change to the input, no matter how small, will cause an unpredictable and wildly different output

- The output is seemingly random, but is actually deterministic (meaning it is calculated and reproducible)

- The output cannot be predicted. It can only be calculated and this takes a measurable amount of work by a computer (and hours with pencil and paper! Don’t do it.)

Now that you understand the basic concept of what a hash is, you can understand the explanation of how Bitcoin mining works.

But before you move on, I recommend you go to an online hash calculator and play with it a little and test for yourself what I’ve said about hash functions. I like this one.

Mining

I will start by demonstrating a concept of work, which is where “proof-of-work” in Bitcoin comes from.

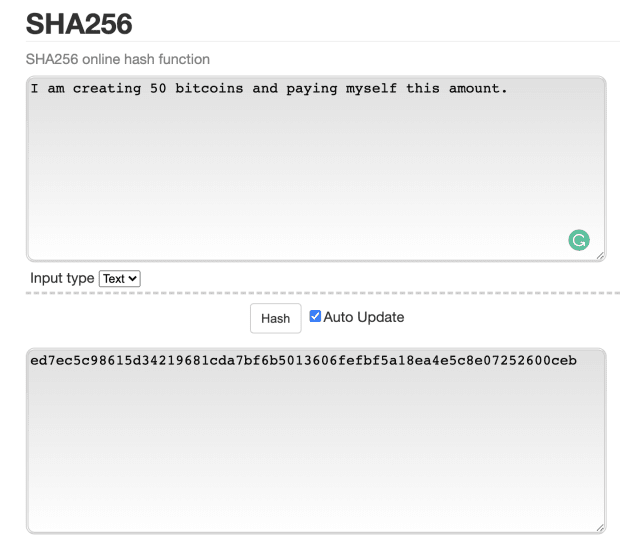

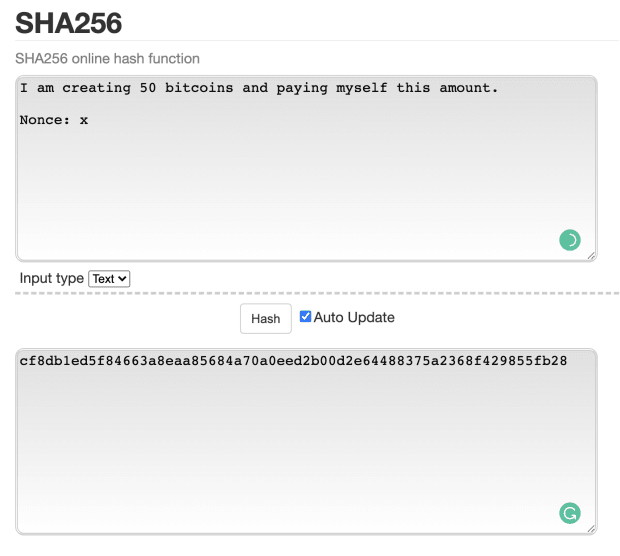

Go to the online hash calculator and type “I am creating 50 bitcoins and paying myself this amount.”

Type it exactly, case sensitive, including the full stop. You should get this output:

Now, let’s create a rule that says for this payment message to be valid, we need the hash to start with one zero. To do that, we have to change the input somehow. But, as you’ve learned, it’s not predictable what the output would be for a given input. What modification can we make to ensure a hash starting with zero?

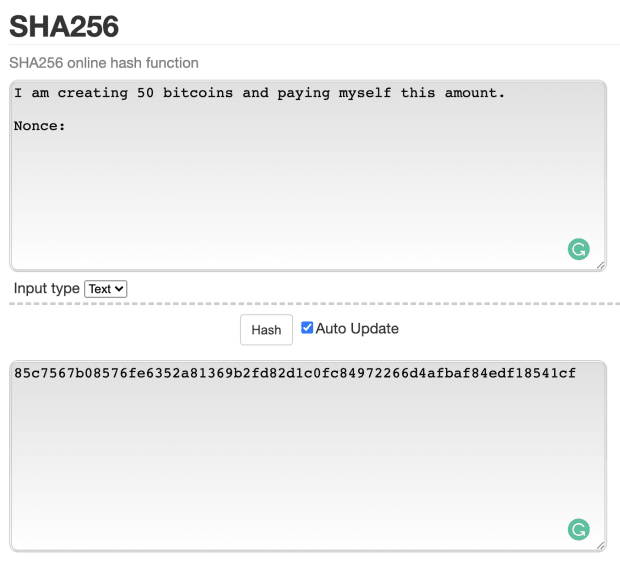

We have to add data using trial-and-error. But we also don’t want to change the meaning of the input message. So, let’s create a field (an allocated section) called a “nonce” which will hold a nonsense value.

The word “Nonce” is supposed to be derived from “number only used once,” but I don’t see it.

Notice below how just adding “Nonce:” as an extra field heading changes the hash output.

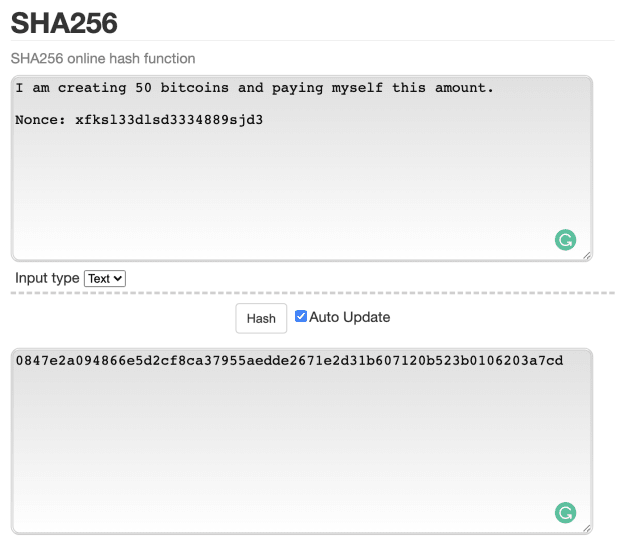

The output still doesn’t start with a “0”, so let’s add some nonsense (I added a meaningless “x”):

It still doesn’t start with a zero. I tried some more characters until the hash started with a zero:

There we go. Now, according to the arbitrary rules I set for this pretend version of Bitcoin, the text in the input window is a valid block with a single transaction paying me 50 bitcoin.

Note that Bitcoin blocks are essentially pages of a ledger. Each block is numbered and creates new bitcoin, along with listing the transactions between users. This record is where bitcoin lives.

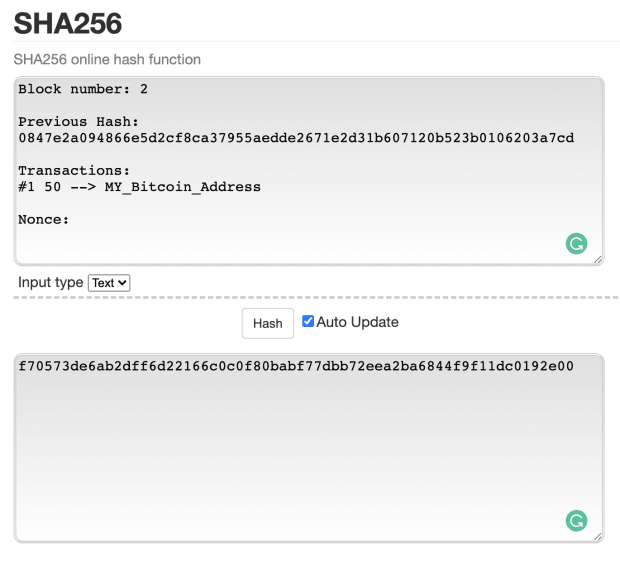

Now a new rule. For the next block, the hash of the previous block must be included. I’ll add a little complexity and add a few more fields to approach what a real Bitcoin block has.

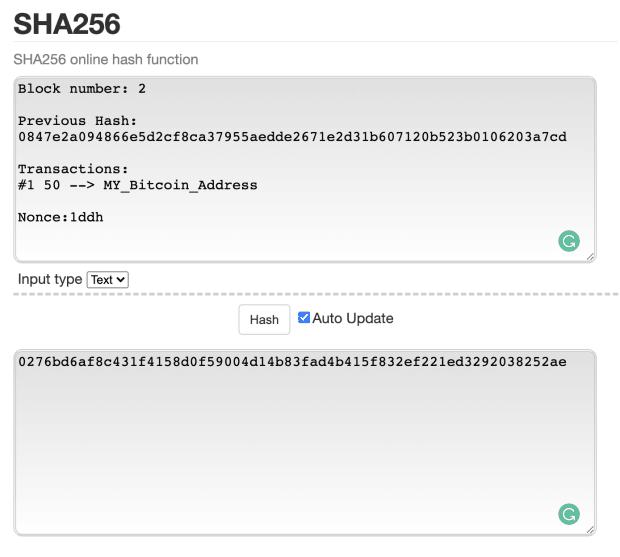

The hash starts with an “f” not “0”, so I’ll have to try some values in the nonce field:

This time I was luckier and found a suitable nonce after only four tries. Recall that for the first block it took 22 tries. There is some randomness here, but generally it’s not too difficult to find a valid hash if all we’re trying to get is one zero. There are 16 possible values for the first hash digit so I have a 1 in 16 chance that any modification I make to the input field will result in the first hash digit being “0.”

Note that Bitcoin’s fields are like this, but there’s more detail that I haven’t added. This is just to illustrate a point, not necessarily to detail exactly what a Bitcoin block looks like.

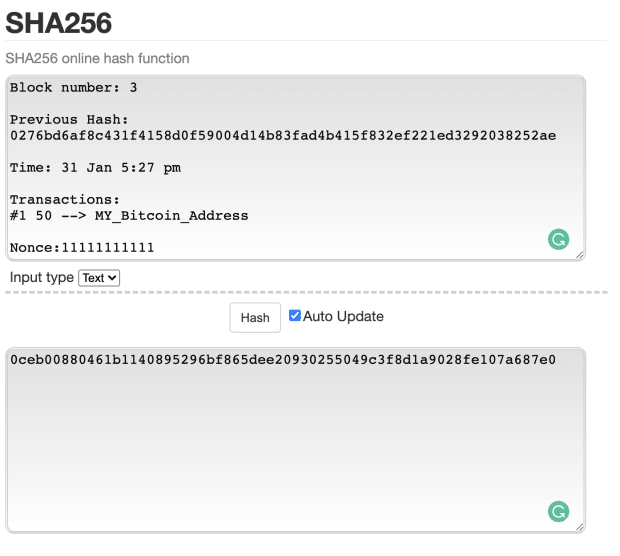

I will add a time field to the next block as I need that to explain the “difficulty adjustment” next:

Above is block number three. It includes the previous block’s hash and now I’ve also started to include the time. The nonce I found successfully made the hash start with a zero (I just kept typing a “1” until the hash target was met).

There’s enough here now that I can start explaining a few interesting concepts about the Bitcoin blockchain and mining.

Winning A Block

The mining process is competitive. Whoever produces a valid block first gets to pay themselves a set block reward. A miner that produces the same block number a bit later gets nothing — that block is rejected. Explaining why that is will cause too much of a diversion now, so I’ll explain it in the appendix.

After block three is found and broadcasted to everybody (all the Bitcoin nodes), all the miners stop working on what would have been their version of block three. They begin to build on top of that successful block three (by pulling its block hash forward into a new block) and start working on finding a suitable nonce for block four. The winner publishes the result and then everyone starts working on block five, etc.

With each block, new bitcoin are being created and collectively make up the total supply so far. If there are many miners, then statistically we should expect that blocks will be produced faster, and therefore bitcoin will be created faster. Problem, right?

Seeking a limited supply of bitcoin with a predictable issuance over time, Satoshi Nakamoto thought of this problem and introduced a negative feedback loop to keep block production at 10-minute intervals on average. How? See if you can think of a way. Pause for a moment and ponder — see if you can come up with the same genius solution and read on when you give up.

NODES: I mention “valid” blocks. So what? Who’s checking? The Bitcoin nodes are. A Bitcoin node keeps a copy of the blockchain so far and follows a set of rules to check that new blocks are within the rules and reject those that aren’t. Where are the rules? In the code. A computer that downloads the Bitcoin code is a node.

The Difficulty Adjustment

The average time to create new Bitcoin blocks is calculated by every node every 2016 blocks (this is why the time field is needed). This is part of the protocol and rules that the nodes follow. A formula is applied to adjust the number of zeros each block hash must start with in order to be valid.

Strictly, it’s not the number of zeros that is adjusted but a target value the hash has to be below, but thinking of leading zeros is simpler to explain.

If blocks are being produced too fast, then the hash target is adjusted according to pre-defined rules that all nodes follow identically (it’s in their code).

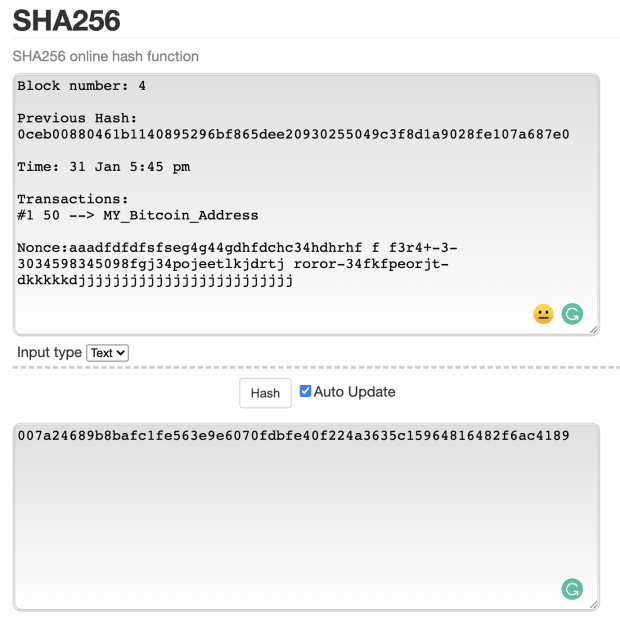

Keeping it simple for my example, let’s say other people are competing with me, blocks are happening too quickly, and now the fourth block needs two zeros instead of one, according to an imaginary calculation.

It’s going to take me a bit longer to get two zeros, but we’re imagining that there are many other people competing with me so the total time taken for anyone to find a block is kept to a target.

Here is the next block:

Notice the time. More than 10 minutes passed since the previous block (I just made the time up to demonstrate). The 10-minute target is probabilistic; it is never known exactly when the next block will be found.

I messed around on the keyboard for a minute until two zeros showed up. This was exponentially harder than finding a single zero. The chance of finding two zeros in a row is 1 in 162, or a 1 in 256 chance.

If more people were to join in the mining and competition for new bitcoin, then eventually three zeros will be required.

I just looked up the last real Bitcoin block, which contains the hash of the previous block. The hash was:

000000000000000000084d31772619ee08e21b232f755a506bc5d09f3f1a43a1

That’s 19 zeros! There’s a 1 in 1619 chance of finding such a block with each attempt. Bitcoin miners do many, many attempts per second, collectively all over the world.

The number of attempts per second is known as the “hash rate.” Currently, the estimated world hash rate is just under 200 million terahashes per second ( one terahash is a trillion hashes). With that many attempts per second, a block with a hash starting with 19 zeros is found around every 10 minutes.

In the future, as more miners join in, the hash rate will go up, blocks will be found faster, and Bitcoin’s difficulty will adjust to require 20 zeros, which will push block production back down to around 10 minutes.

The Halving

When Bitcoin first started, 50 bitcoin were produced with every block. The rules of the Bitcoin blockchain specify that after every 210,000 blocks the reward will be cut in half. This moment is known as “the halving,” and happens roughly every four years. The halving, combined with the difficulty adjustment keeping blocks at 10-minute intervals, means that around the year 2140, the block reward will be 0.00000001, or 1 satoshi, the smallest unit of a bitcoin, and can’t be halved anymore. Mining won’t stop, but the block reward will be zero. From that moment, no new bitcoin will be created going forward and the number of bitcoin is mathematically calculable and close enough to 21 million coins. This is how the total supply is known — it is programmatically set.

Even with the block reward at zero, the miners will still be incentivized to keep working in order to earn transaction fees.

How exactly is the block reward cut in half? It’s in the code held by the nodes. They know to reject any new block after 210,000 where a miner pays himself over 25 bitcoin. And then to reject any blocks after 420,000 where a miner pays himself over 12.5 bitcoin, and so on.

Transaction Fees

So far I’ve only shown imaginary blocks with a single transaction — the transaction where the miner gets paid a reward. This is called the “coinbase transaction.”

It’s not named after the company, Conbase, I mean Coinbase. The company named itself after the coinbase transaction, not the other way around. Don’t get confused.

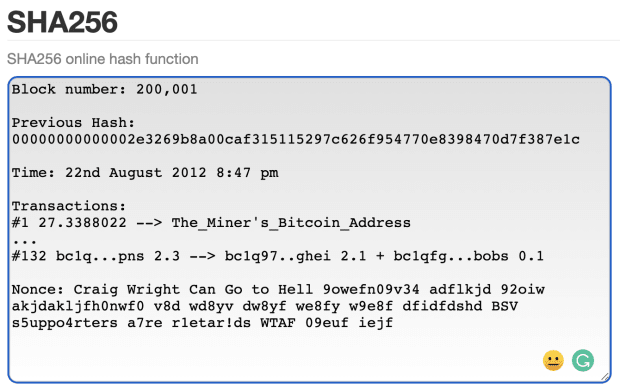

In addition to the coinbase transaction, there are transactions of people paying each other. Here’s an imagined example:

I didn’t bother finding a real hash this time (It’s actually the real hash reported in block 200,001). The nonce I just made up for fun, but notice a message can be embedded there.

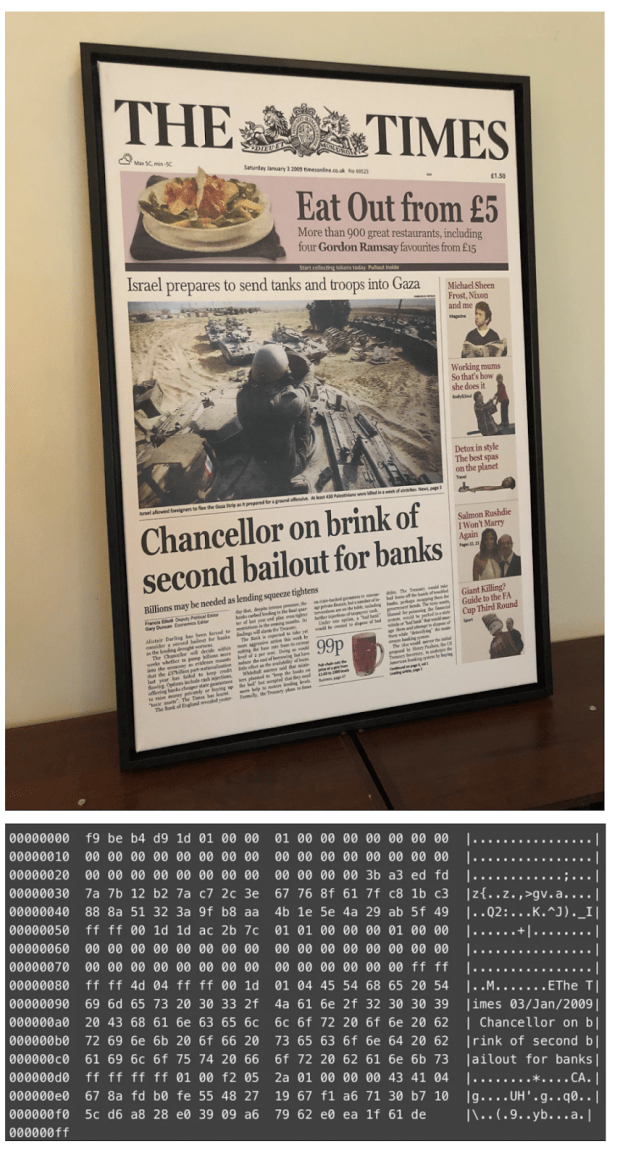

Satoshis famously included the words, “Chancellor on Brink of Second Bailout for Banks” in the first Bitcoin block (The Genesis Block), after the newspaper headline for the day.

The point here is that there are 132 transactions included (not all shown). Look at transaction #132 – 2.3 bitcoin from an address is paying 2.1 bitcoin to another address and also to a second address the amount 0.1 bitcoin (I’ve used dots to shorten the length of the address).

So a source of 2.3 bitcoin pays a total of 2.2 bitcoin (2.2 + 0.1 = 2.2). Is there 0.1 bitcoin missing? No, the difference is claimed by the miner, as I’ll explain.

The miner is allowed to pay himself 25 bitcoin as the block reward (because 210,000 blocks have passed so the reward has been halved from 50 to 25). But if you look, the coinbase transaction is 27.33880022. The extra 2.33880022 bitcoin comes from the other 132 transactions in the block – the inputs will all be slightly greater than the total of the outputs. So the miner gets to claim this “abandoned” bitcoin as payment to himself. These are considered transaction fees paid to the miner.

The block space is limited. When Bitcoin was new, users could send transactions with no fee and the miners would include the transaction in the block. But now there are more users and since getting on the next block is competitive, users include a fee in the transaction to entice the miner to choose their transaction over others’.

So when the block reward steadily goes down, halving every four years and eventually to zero, miners still get paid in this way.

Some have suggested that one day the reward to miners will not be enough and will cause Bitcoin to fail. This concern has been thoroughly debunked and I won’t repeat it here.

Can A Block Be Re-written?

This is extremely unlikely and it’s worth understanding why. You’ll then appreciate why Bitcoin transactions are immutable (unchangeable).

I explained earlier that the hash of the previous block is included in the current block. That means any editing of transactions in an old block changes the hash of that edited block. But that hash is recorded down in the next block, so that means that the next block needs to be updated, too. But if you change the hash recorded in that next block, then its hash needs to change, and so on.

Note that any time a hash is changed, you lose all these lovely zeros and will just be left with a random-looking hash — and have to do all the work again to get the zeros back. If you do that for the block you tried to edit, you then have to redo the work for the next block, and the next all the way to the most recent block. You can’t simply stop at the old block, because the rules of Bitcoin are such that the longest chain of blocks is the real Bitcoin record. If you go back and edit a block 10 blocks ago, you no longer have the longest chain. You have to add 10 more blocks and then a bit more because as you were creating those 10 blocks, the real chain probably became a bit longer. You have to race to overtake the real chain. If successful, then the new version becomes the real version.

Repeating the entire world’s collective hashing effort from the edited block to the latest block is the barrier to editing Bitcoin. The energy was expended to create those hashes with all those improbable zeros and that energy expenditure must be repeated to edit Bitcoin. This is why energy used to mine Bitcoin is not “wasted”; it is there to defend Bitcoin from edits, to make the ledger immutable without needing to trust a central authority.

What happens if two miners find a block at the same time?

This actually happens every now and then, and it always sorts itself out as follows:

Every node will receive either one of the new nearly-simultaneous blocks first and will accept that one and reject the one arriving just moments later. This results in a split of the network, but it’s temporary.

To illustrate, let’s call one of the blocks blue and the other red (they have no color, just bear with me).

Miners then work on the next block, but there will be a split as to which block they extend the chain from.

Let’s say the winning miner found a block using the blue chain. They will send the new block to all the nodes and the longest chain will be apparent. The nodes that had accepted the red chain will then drop it and adopt the blue chain.

All miners that were working on the red chain will stop and will now work on the longer chain, which is the blue chain. The red chain is dead.

Appendix

Why A Runner Up Miner’s Block Is Invalid

Suppose block 700,000 just got mined by MINER-A. Thirty seconds later, MINER-B also created a different version of block 700,000. When MINER-B broadcasts this alternative, every node is going to reject it because they have already seen and accepted the block by MINER-A. What’s more, in that 30 seconds, let’s say that MINER-C found block 700,001. Given that MINER-B’s competing 700,000th block does not extend the current chain (which is up to 700,001), it is also rejected for that reason.

Even more interesting is that if MINER-B had been working on block 700,001 instead of a competing version of 700,000, they would have had just as much chance of mining a valid block 700,001 as they would have to finally find an alternate block 700,000. So as soon as any miner sees a new block, they should set their effort on the next block.

If, however, Miner-B found block 700,000 one second after MINER-A did, then it’s possible that some nodes see MINER-A’s block first while others see MINER-B’s block first, depending on geographic locations and internet speeds. In that case, there is a temporary fork, and some miners will be working to extend one version while other miners will be working to extend the other. As explained earlier using the “blue chain” and “red chain” descriptors, eventually one of the versions will extend further before the other and become the valid version unanimously.

This is a guest post by Arman The Parman. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.